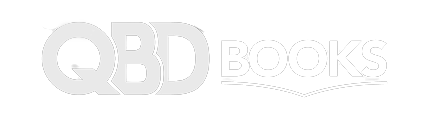

How did rum run the colony?

Words like ‘addiction’ or ‘alcoholic’ were not really considered in colonial Australia. Instead people just ‘needed’ rum to get through the day, or to forget the one they just had. It was not long before there were two classes of people in the colony: those that sold rum and those that drank it.

The marines that travelled on the First Fleet petitioned to ensure they had enough rum with them, insisting on, ‘a moderate distribution of the above-mentioned article being indispensably requisite for the preservation of our lives.’ The marines nagging paid off and so while the meticulous Governor Phillip ensured the colony had enough food for two years, the marines ensured they had enough rum for four; almost 250 litres each.

Though Phillip kept a tight rein over rum’s distribution, when he left in December 1792 rum, and the newly arrived NSW Corps – soon to be dubbed the Rum Corps – took over the running of the colony. Rum became a prized commodity, and as there was no real alternative it also became a de-facto currency.

By the time Governor John Hunter arrived in late 1895 the Rum Corps had had control of the colony for almost three years. Both Hunter and his successor, Philip Gidley King, were recalled primarily because they failed to wrestle back control of the colony from the Rum Corps.

But how could Hunter or King win? Who would police the police? Would a Corps officer arrest one of his own? And on the few times Hunter or King did manage to have an officer charged, would a jury consisting of more Rum Corps officers convict him? Ensuring both settlers and convicts were addicted, the Rum Corps meted out the liquor just enough to keep them wanting more and to keep the price high.

Australia’s first chaplain, Reverend Johnson, despite pontificating about the evils of spirituous liquors, had Australia’s first church built by convict labour paid in rum and flour. He complained, however, that he was paying the Corps 12 times what he knew they were buying it for.

Others sold their farms or livestock. Hunter issued 350 land grants during his governorship but by the time he left in 1800 only 90 of these grants were still with their initial recipients. The Corps had purchased most of the rest for a meagre few gallons. Likewise, many sold their harvest to the Corps and, as Hunter explained to the Colonial Office in London, ‘the produce of a whole year has been thrown away for a few gallons of bad spirit.’

The present-day Sydney suburb of Pyrmont, now the home of the city’s casino, was sold by a desperate drunk for a measly gallon, or 4.5 litres, of rum. Another drunk was so much in need of the stuff he offered to sell his wife for four gallons. In an effort to curb the amount of rum coming into the colony, King imposed an import duty on it, but guess what was used to pay that?

The perceived failure of both Hunter and King led to England sending a governor that they knew would not let them walk over him. Enter the infamous William Bligh, whose ruthlessness and foul mouth was such that it reportedly brought the outgoing Governor King to tears.

It took less than 18 months for the Corps to overturn Bligh in what is now referred to as the Rum Rebellion. It cost Bligh his job but finally the authorities came to understand just how much power the Rum Corps had in its most distant colony. The Rum Rebellion led to the Corps being recalled. This meant that although the extortionate prices that rum was selling for abated, the amount of rum consumed remained as it was.

To use this thirst to his advantage, Governor Macquarie agreed to let three entrepreneurs build him a much-needed hospital if they were permitted a monopoly on the trade of rum for three years. The businessmen ultimately lost on the deal, and the hospital they build was so shoddy that much of it had to be rebuilt. Such novices were the three they even neglected to install toilets.

Macquarie also suggested to England that the colony be allowed to build its own distillery on the basis that if the locals were so intent on spending all they had on alcohol, it would be foolish to let the profits go ashore instead of being used to benefit the colony. By the time the authorities in England had warmed to the idea, Macquarie had been replaced by Governor Brisbane who, though instructed to build the distillery, considered it, ‘the worst step that was ever adopted.’

Brisbane proved to be right. Over the next two decades the amount of rum drank per person more than doubled, from 14 to 31 litres per person per year. It was only the depression of the 1840s and the subsequent end of convict transportation that saw rum consumption decline. Since then, alcohol has not controlled Australia to the same extent, but it has remained a great influence and even a misplaced source of national pride.

Australia’s first prime minister, Edmund Barton, was known as ‘Toby Tosspot’ for the amount of booze he could put away, and drinking records held by cricketers (David Boon: 52 cans on a flight to London) and another prime minister (Bob Hawke: a 2.5 pint yard glass in 11 seconds) are often more fondly recalled than their sporting or political achievements.

Rum: A Distilled History of Colonial Australia by Matt Murphy is published by HarperCollins and is available in paperback and e-book.