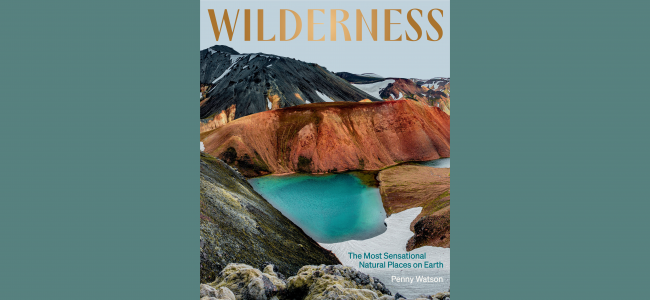

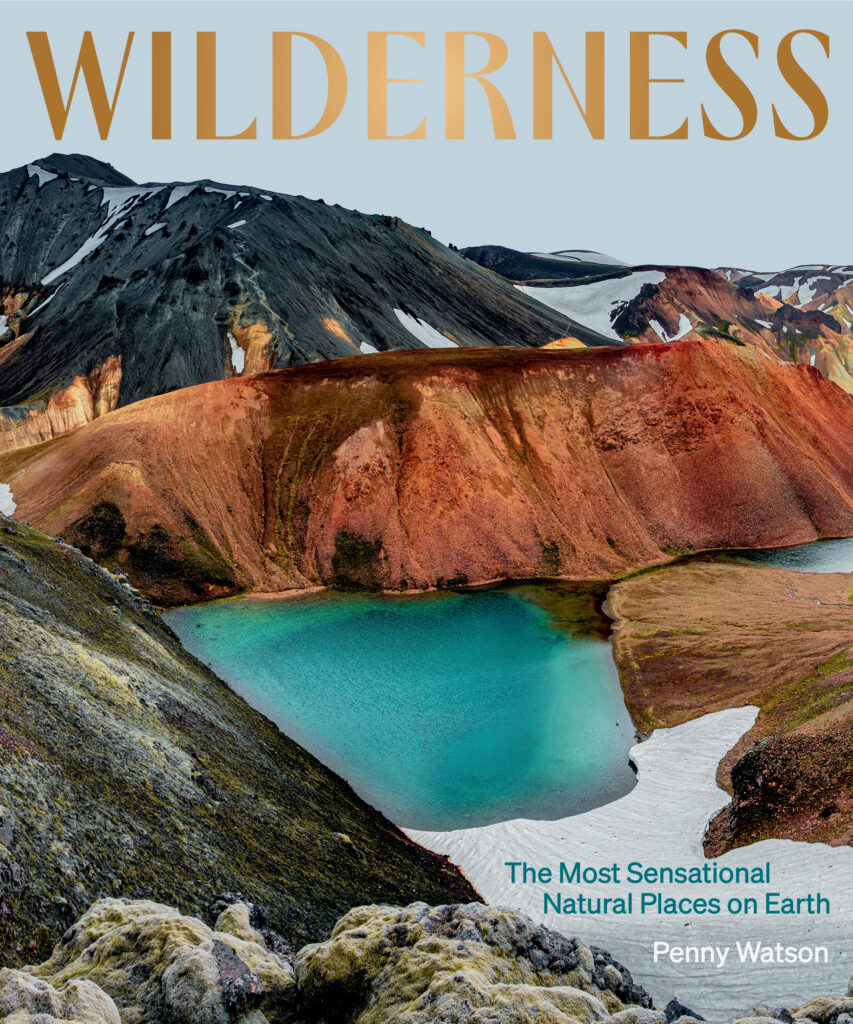

“Wilderness: The Most Sensational Natural Places on Earth” by Penny Watson is a stunning hardcover book perfect for your coffee table, and of course, to inspire you for your next big adventure.

This must-have non-fiction title is a dreamy and riveting coffee table book featuring 40 of the most glorious wilderness destinations on our Earth, both the widespread and uninhabitable and those that exist within close proximity of civilisation.

This book will be a source of wanderlust and motivation, and a reminder to safeguard the precious beauty and sanctity of our home.

Our QBD Blog Readers have access to an extract from this wonderful book. Keep reading to find out more about “Wilderness” and see how this title will be a great fit for you and your home.

INTRODUCTION

We live in a time of dawning truths that tell us Planet Earth’s greatest commodity is not its iron-ore deposits, its towering skyscrapers or its 21st-century infrastructure, rather its wilderness – the world’s wildest, most wondrous and increasingly rare natural places that have endured despite humanity.

Wilderness. The word itself is powerful and emotive, conjuring images that loop on our social media feeds: misty forests, clear sparkling streams, the sun’s shadow falling across a desert dune, a glistening blue Arctic peak, polar bear cubs walking across a tundra, a whale breeching the surface of a sun-flecked ocean.

That our popular culture – and imaginations – habitually freestyle to these destinations says much about their place in our psyche. In times of inner turmoil or outer chaos they are a clarion call. When we want adventure they are freedom calls to strap the walking shoes or backpack on. When we seek quietude, inner peace, renewal, they ignite a dormant instinct to be in nature; a yearning that many of us have been slow to fully understand.

Somehow, the increasing insularity and urbanity of our lives have made this call to the wild louder, stronger, more urgent. We are increasingly aware of the climate crisis and the havoc that humanity has reeked on the planet. Our mental and physical need for nature, in our own backyards as much as in wild outposts, can be read as a quiet rejection of our footprints on a fragile planet, even a call to arms.

But what is a wilderness?

The question has trailed me during the research and writing of this book. When first conjuring wilderness, my mind went to untamed, untrammelled places, those wild and remote destinations untouched by humanity where the modern world is out of mind and out of sight. But in the face of a climate crisis, not many such places truly exist anymore. This idea of wilderness is mostly obsolete.

I got to thinking, too, that wilderness areas cannot simply be zoos for the natural world, where we zoom in to see what our wild Earth once looked like. Wilderness areas are both those natural wondrous places captured in the cross-hairs of our binoculars, as well as those doorstep destinations that we are more likely to have intimate encounters with. They are both the places that are still wild in the traditional sense, and those that, though impacted by humanity, have a chance to regenerate, rewild and recover through our own protection, conservation and activism. This could well be the unseen role in the modern-day world of the wilderness that still remains.

The conundrum between wilderness and tourism is not lost on me. Doesn’t promoting wilderness areas in the travel space jeopardise these very destinations? The answer – both yes and no, is complex. Tourism can be at once part of the problem, and a force for good. There are many destinations within this book that have relied on, do rely on or will rely on the tourism of the future for their future because of its role in providing jobs and revenue in local communities, furthering conservation efforts, funding research and spreading awareness, particularly where wildlife is concerned. Uganda’s gorillas and Madagascar’s lemurs come to mind.

Some destinations, such as Fiordland National Park, in Aotearoa New Zealand, are notable and included for flagging a more sustainable future for tourism. They are destinations we can learn from. Others, such as Zhangjiajie National Forest Park in China, can at once be lauded for their beauty and recognised as places where fewer people should tread. Given the complexities of the conservation–tourism dynamic in each destination, I have aimed to inspire stewardship of nature as well as the yearning to travel.

Wilderness is part travel inspiration, part lounge chair eye-candy, part battle cry. It is for those of us who choose slow and responsible travelling, those of us who love the outdoors and natural immersion, and those of us concerned for the planet in the face of the climate crisis. It is for those in the sweet spot where all these interests intersect.

There are 40 destinations in this book that take you to some of the most sensational wilderness areas around the world in all their full-blown magnificence. The wildernesses reference many types of natural habitats, from diverse land-based environments to oceans and rivers, all remarkable, and threatened, in similar ways.

If the extreme heat and arid sands of a desert can be called a wilderness, if the coral cays and islands of an archipelago can be called a wilderness, if the wet humidity of a rainforest can be called a wilderness, then the magnitude and volume of the ocean’s waves and the currents, trenches and weather systems that bring them to life also deserve a place in the canon.

Many of these wildernesses have extraordinary wildlife, ecology and biodiversity. Whether you want to armchair travel or pack your bags, these destinations include information about conservation and regeneration alongside opportunities for travellers to tread more lightly while travelling to the world’s wild places.

The book is best savoured by dipping into different chapters at random. In the Southern Hemisphere, you can journey from the untamed Kimberley coastline of Western Australia and the wild Franklin River in Tasmania to the desolate Salt Flats of Bolivia, and the flourishing Pantanal wetlands of Paraguay. In the Northern Hemisphere, you can touch down in the other-worldly geology of Bisti/De-Na-Zin Wilderness and the tall trees of California’s redwood forest in the United States, and on the icy tundra of Canada’s remote Churchill community – where you can marvel at polar bears in the wild.

The aquamarine reefs of Australia’s Ningaloo, the white-to-the-horizon polar desert of Antarctica, the green tropical rainforests of Indonesia and the red sand landscape of Jordan’s Wadi Rum are all here waiting to be explored at your leisure.

What does it feel like to completely surrender to the natural world, to bow to its power, to be humbled by its force, to know that it can overwhelm, dictate, besiege? Over time, Antarctic and Arctic expeditioners, ancient mariners and explorers of the planet’s mighty mountains have all been able to describe the immensity of it, that liminal space where we humans are relegated to our rightful place as subjects of a mightier force. Natural phenomena are bewildering in their improbability. That places so other-worldly, freely delivered by nature on such a grand scale, can continuously inspire humanity says something about our ongoing connection to that which is beyond our comprehension.

These wilderness destinations still ignite such feelings within us. They evoke a sense of timelessness and are sources of healing and wellness in times of upheaval.

Wilderness is not a guidebook, more a jumping-off point for your own curiosity, interest and intrigue. Whether these wilderness destinations spark a flight of fancy and an urge to travel or not, they will give you an appreciation of nature at its most poignant, and most importantly of all, I think, a willingness to protect it. It’s all we’ve got.

[FROM PAGE 117]

Many years ago, when I moved home to Australia after an absence of 10 years, I vowed to explore my own country, to adventure out into the far reaches of the huge island continent that had, until then, played second fiddle to the great many wonders I’d seen in the rest of the world. If I had known what I was missing, I might not have left the country in the first place. That said, Aotearoa New Zealand is so proximate to Australia, relatively speaking, that forays across the pond were inevitable.

Australia is the Earth’s smallest continent, but it is breathtakingly big on wilderness. From its central red desert landscapes brimming with extraordinary native wildlife to its ancient rainforests and shimmery blue reefs, it has a diversity of flora, fauna and habitat that is unmatched. Australia is also home to the oldest continuous living culture on Earth – that of First Peoples dating back at least 65,000 years.

The Australian wildernesses I have chosen for this book come from all corners of this great land, stretching from the Kimberley coastline in the west and the Great Barrier Reef in the tropical far north right down through the Central Red Desert to the wilderness of south-west Tasmania/lutruwita. From the exceptional number of wilderness destinations in Aotearoa New Zealand, Fiordland National Park on the South Island, stands out for its mountainous peaks, deep tannin waters and unique wildlife.

Some of these destinations require dedicated travel, such is their remoteness; some have wild landscapes and dangerous creatures; all are worthy of your time, energy and resources. You might not be able to see them all in one lifetime but visiting one, maybe two, mindfully, and with sustainability in mind, is the new zeitgeist.

NINGALOO REEF

Western Australia

Coral reefs, an eco ethos and the big three – mantas, humpbacks and whale sharks.

It’s hard to credit just how remote the UNESCO World Heritage–listed Ningaloo Reef is. Mid-way up the never-ending west coast of Western Australia, the reef’s Traditional Owners are the Jinigudera Peoples of the Thanalyji, who have lived here and cared for these waters for millennia. The reef is near the tiny gateway towns of Exmouth and Coral Bay but an eye-watering 13-hour drive (1200 kilometres/750 miles) north of the nearest city of Perth. From Perth, Sydney is more than 3000 kilometres (1864 miles) east as the crow flies. In the other direction, across the endless Indian Ocean, South Africa’s Cape Town is roughly 8700 kilometres (5400 miles) away.

This is surely one of the reasons Ningaloo, the largest fringing reef in the world and one of the last great ocean paradises, has only in the last decade, started to register on the travel radar of Australians. That the Great Barrier Reef (see p. 141) was inscribed by UNESCO as World Heritage in 1981 and Ningaloo Reef only listed in 2011 must have played a part too. Certainly, those living on the east coast have always had the Great Barrier Reef to distract them.

But this is changing.

Happily, it’s often a tale of responsible tourism. Ningaloo is not only a pristine wilderness, but its tourism arm also has sustainability as a priority. Human interactions with animals, such as swimming with whale sharks, are protected and managed by the Western Australia Parks and Wildlife Service, and tourism operators tend to be specialist licensed professionals with a small-group eco ethos. They are aware that Ningaloo’s reputation as a world-beating nature experience is key to its success and longevity. Accommodation offerings, thus far, tend to be small scale. The coveted luxury option, Sal Salis, is an eco-camp in the coastal dunes.

But the reef has other challenges, including, at the time of research, Woodside Energy’s proposed Burrup Hub deep sea gas project, which is ‘the most climate-polluting project currently proposed in Australia’, according to a Greenpeace press release. Coral bleaching in the northern part of Exmouth Gulf (Bundegi) due to unusually hot water being generated off Western Australia’s north-west coast is another alarm bell.

Officially, the UNESCO-listed Ningaloo Coast World Heritage Area includes Cape Range National Park and Ningaloo Marine Park. The latter covers an area of more than 600,000 hectares (2300 square miles) and stretches an incredible 300 kilometres (186 miles) from Northwest Cape to Red Bluff. The wow-factor is its astounding – and pristinely protected – biodiversity, a merging of tropical species to the southern end of their range and temperate species to their northernmost point.

According to the Parks and Wildlife Service its waters are home to approximately 500 species of fin fish, 300 species of coral, 600 species of mollusc and 90 species of echinoderm. It’s astounding to think how important the reef’s seagrass, mangrove and coral habitats are to the health of this marine environment, and indeed marine environments globally.

What adds impact to the destination is the fact that much of this astonishing reef and marine life is located just off-shore. It is accessible direct from a string of beaches along the coastline. On any given day, snorkellers can float over a wonderland of coral and nature’s own aquarium of giant clams, sea turtles and tropical fish.

Those with their sights set on bigger creatures can go further off-shore into the bigger blue. Ningaloo is becoming known as one of those Earthly enigmas where enthusiasts can set eyes on the big aquamarine three – manta rays, humpback whales and whale sharks, all in the one location.

Sightings are reliable too and Tourism WA says Ningaloo has one of the highest interaction rates, sitting above the 90 per cent mark most seasons.

Exact timings depend on whether you are accessing the reef from near Coral Bay or Exmouth. But as a rough guide, mid-March to August is the time to see whale sharks migrating to Ningaloo to feed on plankton and krill.

A swim with whale sharks is particularly special. Wearing snorkel and mask, swimmers trail these gentle marine giants – the ocean’s biggest fish – through the blue haze, watching as they sashay through the sun-flecked ocean depths, their enormous boomerang-shaped tail fins swaying majestically.

From June to October humpback whales pass by on their annual migration for Antarctica. Manta rays are a year-round attraction, their graceful bodies gliding through the water like billowing sheets. If these migration seasons align, you’ve a chance to see them all at the same time.

Ningaloo is one of those rare wildernesses, where early implementation of sustainability and conservation measures have given it a chance of success. It might be remote and tough-going to access, but the effort will be rewarded when a manta ray glides over head or a whale shark materialises in the big blue.

Visit us in-store or online to get your copy of “Wilderness: The Most Sensational Natural Places on Earth” today!